| HEIR/DARRELL Chart 0500 |

![]()

|

|

|

(2)married |

|||

| 1

|

|

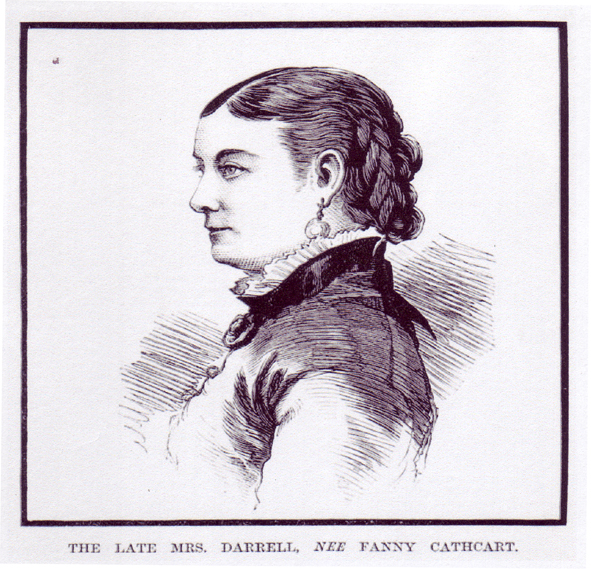

2 MARY FRANCES (FANNY) BLACK CATHCART born about 3rd August 1833 Nottingham, Nottinghamshire baptised 20th December 1835 St Gregory by S Paul City of London occupation Stage Actress died 3rd January 1880 Carlton, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

3 |

||

|

Mary Frances (Fanny) Black CATHCART |

|||||

|

|||||

|

4 unknown HEIR born about ??? died young |

5 unknown HEIR born about ??? died young |

6 unknown HEIR born about ??? died young |

|||

|

The idea of these charts is to give the information that we have found in the research we have done and put together and with the help of many other people who have contacted us over the past thirty odd years we have been researching our family. The idea is that you click on the Chart box in blue to be taken to the next family. There is now a large number of charts to be found and connections can be made to all the main families I am researching. If a chart has a box with the standard background it means that as yet I have not put the Chart on the Web.

To conform to the Data Protection Act

all the Charts have been altered to exclude all details for living

people other than the name.

![]()

If you have comments, alterations, corrections, amendments etc. please follow the details to be found on the Home Page to contact me.

Last updated Monday, November 21, 2011 15:34